What’s different this time?

All eyes have turned to the northwestern part of the country, where cases of Ebola virus disease emerged this month, leading to an outbreak declaration and quickly posing a "very high" public health risk.Though it's too early to determine what the outcome of this outbreak could be and how wide it could spread, there is one aspect that many experts agree on: The world seems better prepared than ever to fight this outbreak."We are hearing about this and supporting a response to it much more quickly than the three-country outbreak in 2014-16," said Dr. Anne Schuchat, principal deputy director of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.The Ebola outbreak in West Africa between 2014 and 2016 was the largest and most complex on record since the virus was discovered in 1976. That outbreak, which started in Guinea and spread to Sierra Leone and Liberia, saw more cases and deaths than all other Ebola outbreaks combined, according to the World Health Organization. During that outbreak, a total of 28,616 cases of Ebola virus disease and 11,310 deaths were reported in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone — as well as an additional 36 cases and 15 deaths that occurred when the outbreak spread outside of those three countries, according to the CDC. Then, "there were lots of criticisms of the WHO response," Schuchat said. Now, however, WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus already has visited the affected areas."Thepolitical level at the national, regional and global level is committed to support this," Schuchat said of WHO's response this year.Additionally, "the Democratic Republic of Congo has had Ebola outbreaks before. This is the ninth one. This is a serious one in that it's not just in a rural area but has reached an urban area, but there is more familiarity with the disease and syndrome than there was in West Africa," Schuchat said. Also, in the 2014-16 outbreak, research was just beginning to test Ebola vaccines and drug candidates in humans."We now have very good experience with one of the vaccines that was tested in the ring vaccination trial in Guinea and was also tested in large studies in Sierra Leone and Liberia, and appears to be very effective and very safe," she said. "We don't have licensed vaccines or drugs yet, but we have very promising vaccine and drug candidates."

'We now have tools'

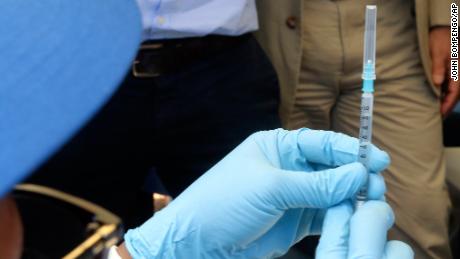

Authorities are distributing the experimental Ebola vaccine rVSV-ZEBOV in Mbandaka, a city of nearly 1.2 million people in northwestern Congo's Equateur province. In the 2014-16 outbreak, researchers were in the very early stages of developing possible vaccines, and testing began only in the final days of that outbreak.Between 2015 and 2016, the rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine was given to people in Guinea who were in contact with patients who had recently confirmed cases of Ebola virus disease, according to a study on that trial published in the journal The Lancet. "The rVSV vaccine was used in the ring vaccination program in Guinea," said Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, who oversees an extensive research portfolio that includes studies on the Ebola virus."Ring vaccination means you identify someone who has Ebola, and you identify the contacts of that person and the contacts of the contacts, and you vaccinate them with the rVSV vaccine. That is the major difference between the beginning of the outbreak in West Africa and what we're seeing now," Fauci said. "We had no tools then, and by the time we had the vaccine ready to test, most of the cases had burned out," he said. "We now have tools."There are five known Ebola virus species, named after the regions where they originated, and three have been responsible for the larger outbreaks in Africa: Zaire ebolavirus, Bundibugyo ebolavirus and Sudan ebolavirus. The rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine, from the pharmaceutical company Merck, covers the strains in the Zaire group.The doses that Merck sent to WHO to help in the current outbreak were donated. Spokeswoman Pam Eisele said Tuesday that the company plans to file for licensure of the vaccine next year.

"The rVSV vaccine was used in the ring vaccination program in Guinea," said Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, who oversees an extensive research portfolio that includes studies on the Ebola virus."Ring vaccination means you identify someone who has Ebola, and you identify the contacts of that person and the contacts of the contacts, and you vaccinate them with the rVSV vaccine. That is the major difference between the beginning of the outbreak in West Africa and what we're seeing now," Fauci said. "We had no tools then, and by the time we had the vaccine ready to test, most of the cases had burned out," he said. "We now have tools."There are five known Ebola virus species, named after the regions where they originated, and three have been responsible for the larger outbreaks in Africa: Zaire ebolavirus, Bundibugyo ebolavirus and Sudan ebolavirus. The rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine, from the pharmaceutical company Merck, covers the strains in the Zaire group.The doses that Merck sent to WHO to help in the current outbreak were donated. Spokeswoman Pam Eisele said Tuesday that the company plans to file for licensure of the vaccine next year.  "We can now give this vaccine to people at most risk of getting Ebola, such as health care workers treating Ebola patients and contacts of Ebola cases. The hope is that this would contain the spread of the virus. The key difference in this latest outbreak here is that the vaccine is being used in the early stages of the epidemic," said Connor Bamford, a postdoctoral research assistant with the Medical Research Council at the University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research in Scotland.On the other hand, "vaccines aren't so effective at curing you of a disease if you are already infected," he said. "There are no such licensed antiviral medicines against Ebola. There are, however, experimental drugs available."

"We can now give this vaccine to people at most risk of getting Ebola, such as health care workers treating Ebola patients and contacts of Ebola cases. The hope is that this would contain the spread of the virus. The key difference in this latest outbreak here is that the vaccine is being used in the early stages of the epidemic," said Connor Bamford, a postdoctoral research assistant with the Medical Research Council at the University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research in Scotland.On the other hand, "vaccines aren't so effective at curing you of a disease if you are already infected," he said. "There are no such licensed antiviral medicines against Ebola. There are, however, experimental drugs available."

The experimental drugs that offer hope

Experimental Ebola drugs — including ZMapp, favipiravir and GS-5734 — are available for Congo's Ministry of Health to access if needed to treat patients in the current outbreak.In 2014, ZMapp was used to treat two American missionary workers, Dr. Kent Brantly and Nancy Writebol, who contracted Ebola in Liberia. Previously, the experimental drug had been tested only in monkeys.That year, Teresa Romero Ramos, a nurse's aide who contracted the virus while caring for Ebola patients in Spain, was treated with an IV drip of antibodies from an Ebola survivor as well as favipiravir.A study published last year in the Journal of Infectious Diseases reported a case in which a newborn contracted an Ebola virus infection from its mother; the baby was treated with both ZMapp and GS-5734 and survived. The patient was the first newborn known to survive a congenital infection with Ebola virus.GS-5734 "is a drug that we have experience with because we have a protocol that we implemented in West Africa where we tried to suppress or eliminate the residual Ebola virus in the semen of survivors," Fauci said. That protocol is still being used in West Africa.He added that at the National Institutes of Health's Vaccine Research Center, another drug was developed: mAb114, which is in a phase one trial."The minister of health of the Democratic Republic of the Congo has requested accessibility to that antibody," Fauci said. "We are willing to provide mAb114 to them, and we are working with the health authorities in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and in coordination with the WHO to determine if this is feasible."Bamford pointed out that these experimental drugs are offering hope for controlling not only the current outbreak but outbreaks to come."We should strive to get antivirals for Ebola licensed not only to save lives but to offer more to communities who might fear that Ebola is incurable and would otherwise not report their infection to authorities," he said. "Antivirals provide hope to those infected, and perhaps ZMapp, favipiravir and GS-5734 are those medicines, but we don't know yet."Though many of those drugs were used in the 2014-16 outbreak and showed promise, questions remain about their clear effectiveness in decreasing either symptoms or likelihood of death, said Dr. Bruce Ribner, a professor at the Emory School of Medicine who led the university's team in treating Ebola patients in 2014. He was among the five Ebola doctors listed that year as Time magazine's Person of the Year."The only clear difference that I see between this outbreak and the 2014-2016 outbreak is the more robust response to this outbreak that was lacking in the spring of 2014, with the earlier introduction of vaccines, therapeutics and outside health care workers to assist," Ribner said. "We are also somewhat more fortunate in that the Congo has lived with Ebola."

'Each new outbreak teaches us a new lesson'

Ebola is endemic to Congo, and this is its ninth outbreak of Ebola virus disease since the discovery of the virus near the country's Ebola River."So they are extensively experienced in how to handle an Ebola outbreak," Fauci said.Compared with the 2014-16 outbreak, "that's a big difference, because in West Africa — in Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea — that was the first time that they had ever experienced Ebola," he said.Many experts — including Dr. Susan Kline, an associate professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota Medical School — hope that the lessons of the 2014-16 Ebola outbreak will not be forgotten."During the last outbreak, it was felt in retrospect that probably the local, national, international response to the outbreak was not as rapid and as widespread as it needed to have been to prevent the outbreak from becoming so large," said Kline, a member of the Infectious Diseases Society of America's Public Health Committee. "I think people have learned from that experience, that to get an outbreak under control, you really have to work quickly, not only to identify and isolate in Ebola treatment centers and treat patients, but then also do the community outreach work to identify contacts," she said. In response to the Congo outbreak, the US has deployed some Ebola experts from the CDC to help with control efforts, such as screening and tracing Ebola cases, Schuchat said.She added that the CDC has an office in Congo, where workers have shifted their duties to assist in the outbreak. Other organizations also are leading efforts in clinical care and outbreak control, she said, such as Medecins Sans Frontieres (Doctors Without Borders), UNICEF and USAID.All in all, "we know that we have the tools available to control outbreaks now and in the future. We know that we cannot be complacent," Bamford said. "We still do not know all there is to know about the Ebola virus, and each new outbreak teaches us a new lesson, such as the virus' ability to lie dormant in some rare patients where it may flare up years later," he said. "With Ebola, we must expect the unexpected."

In response to the Congo outbreak, the US has deployed some Ebola experts from the CDC to help with control efforts, such as screening and tracing Ebola cases, Schuchat said.She added that the CDC has an office in Congo, where workers have shifted their duties to assist in the outbreak. Other organizations also are leading efforts in clinical care and outbreak control, she said, such as Medecins Sans Frontieres (Doctors Without Borders), UNICEF and USAID.All in all, "we know that we have the tools available to control outbreaks now and in the future. We know that we cannot be complacent," Bamford said. "We still do not know all there is to know about the Ebola virus, and each new outbreak teaches us a new lesson, such as the virus' ability to lie dormant in some rare patients where it may flare up years later," he said. "With Ebola, we must expect the unexpected."

CNN's Natalie Gallon, Euan McKirdy, Al Goodman and Susan Scutti contributed to this report.

Original Article

[contf] [contfnew]

CNN

[contfnewc] [contfnewc]